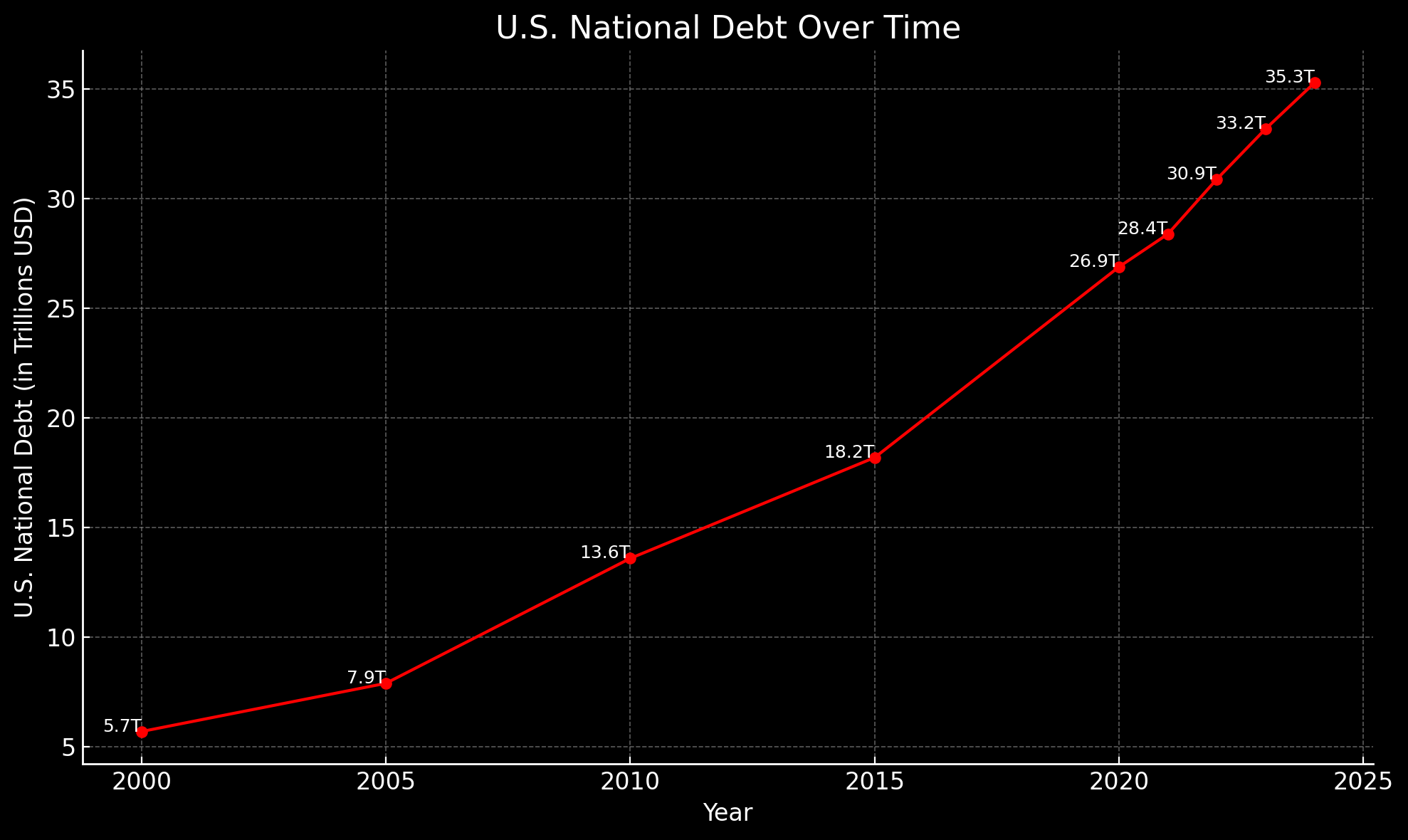

Traditional Finance

Reasons For U.S. National Debt

-

The U.S. national debt is influenced by a combination of factors, ranging from government policies to economic events. Here are the primary causes:

1. Deficit Spending

- The most fundamental cause is when annual government expenditures exceed revenues. The U.S. government consistently spends more than it collects through taxes, resulting in budget deficits that accumulate over time.

- The gap between government revenue and spending is filled through borrowing, adding to the national debt.

2. Major Economic Stimulus Programs

- COVID-19 Pandemic Relief: Massive government spending during the pandemic, such as the American Rescue Plan and other stimulus programs, increased debt significantly, pushing the national debt to new highs.

- 2008 Financial Crisis Bailouts: Programs like the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) were used to stabilize the economy during the financial crisis, adding trillions to the debt.

3. Tax Cuts Without Equivalent Spending Cuts

- Tax cuts reduce government revenue, but if not offset by spending cuts, they increase deficits and debt. Examples include:

4. Defense and Military Spending

- The U.S. has one of the highest defense budgets in the world. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, increased defense spending post-9/11, and continued military modernization have contributed significantly to the debt.

- Military expenditures grew rapidly during the early 2000s and spiked again during conflicts like the Iraq War.

5. Mandatory Spending Programs

- Social Security and Medicare: These are the largest components of the federal budget and continue to grow due to the aging population.

- As the Baby Boomer generation retires, spending on these programs increases dramatically, with no corresponding increase in revenue.

6. Interest on Existing Debt

- As the national debt grows, so does the cost of servicing it through interest payments.

- The U.S. spends hundreds of billions each year just on interest payments, making it one of the largest budget items. As interest rates rise, this cost will also increase.

7. Emergency and Disaster Relief Spending

- Natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, wildfires) and emergency measures add unplanned expenditures.

- Programs like unemployment insurance expansions during economic downturns also contribute.

8. Economic Recessions and Lower Revenue

- During recessions, tax revenues fall as businesses and individuals earn less, while the need for government assistance increases (e.g., unemployment benefits).

- This leads to higher borrowing and increased debt.

9. Political Gridlock and Debt Ceiling Crises

- Disagreements over budget priorities and raising the debt ceiling can lead to temporary government shutdowns or uncertainty, which disrupts financial planning and often results in increased borrowing.

10. Healthcare Costs

- Healthcare programs like Medicaid have also grown significantly over the years.

- Rising healthcare costs in general put pressure on federal spending, contributing to higher deficits.

11. Unfunded Wars and Emergency Spending

- Wars, such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan, were funded through borrowing rather than cuts in other areas or tax increases, adding trillions to the debt over time.

Key Takeaway

The biggest drivers of the U.S. national debt are structural deficits driven by tax and spending imbalances, large-scale economic programs, and increasing costs of mandatory spending. To reduce the debt, the government would need to address these core issues, which often involves politically difficult decisions like raising taxes or cutting spending on popular programs.

Hyper Inflation and Dedollarization

-

The combination of a high national debt and its related economic pressures can potentially contribute to unprecedented inflation and even the risk of "dedollarization," where the U.S. dollar loses its status as the world’s dominant reserve currency. Let’s break down the potential pathways and mechanisms that could lead to these outcomes:

1. Debt Monetization and Excessive Money Supply Growth

- Debt monetization occurs when a government finances its debt by printing more money instead of borrowing through bonds. This approach increases the money supply drastically.

- With more dollars in circulation, the purchasing power of each dollar decreases, which can lead to high inflation or even hyperinflation if not controlled.

- Historically, countries like Zimbabwe and Venezuela experienced runaway inflation when their central banks printed large amounts of money to cover deficits and debt.

2. Rising Interest Payments Leading to Higher Borrowing

- As the national debt grows, so do the government’s interest obligations. When interest payments consume a larger share of the federal budget, the government may need to borrow even more to meet these payments.

- This borrowing can become a vicious cycle, where the government needs to issue new debt to pay off old debt, leading to increasing total debt and rising interest costs.

- If investors see this cycle as unsustainable, they may demand higher interest rates to compensate for the perceived risk, leading to higher borrowing costs and even more borrowing—driving up inflation.

3. Loss of Confidence in the Dollar and Its Value

- The national debt’s sheer size can shake confidence in the U.S. government’s ability to manage its finances, especially among foreign investors.

- If investors lose faith, they may begin to sell off U.S. assets or avoid holding dollars, triggering a currency depreciation.

- A weakening dollar makes imports more expensive, leading to imported inflation. As the dollar’s value falls, prices rise, leading to inflationary pressures across the economy.

4. Potential Shift in Global Reserve Currency Status

- Currently, the U.S. dollar serves as the world’s primary reserve currency, meaning central banks and governments around the world hold dollars to conduct international trade and maintain stability.

- If the U.S. continues to accumulate unsustainable levels of debt, countries may start to look for alternatives, such as the Euro, the Chinese Yuan, or even digital currencies.

- A major shift away from the dollar as a reserve currency (i.e., dedollarization) would drastically reduce demand for dollars, causing a sharp depreciation in its value.

- A sudden loss of reserve status could cause hyperinflation within the U.S. economy, as the influx of repatriated dollars would dramatically increase the domestic money supply.

5. Foreign Selling of U.S. Debt

- Foreign governments and investors currently hold a large portion of U.S. Treasury debt (e.g., China and Japan). If these countries start selling their holdings due to concerns over U.S. debt sustainability, it would flood the market with Treasuries.

- A massive sell-off would push up yields, making it much more expensive for the U.S. government to issue new debt.

- This could lead to a spiral of rising interest costs and further debt issuance, undermining the value of the dollar and leading to a loss of investor confidence.

- In response, the Federal Reserve might intervene by purchasing the debt (monetization), which, as discussed, would further inflate the money supply and contribute to high inflation.

6. Hyperinflation Scenario from Lack of Fiscal Control

- If the U.S. government continues running high deficits without a credible plan to control spending or increase revenues, investors may demand much higher yields or stop lending altogether.

- To avoid a fiscal crisis, the government might resort to monetizing its debt, printing money to cover deficits, which can lead to a hyperinflationary spiral.

- In a hyperinflation scenario, prices can skyrocket rapidly, leading to a loss of faith in the currency itself, which accelerates dedollarization.

7. Geopolitical Factors and Weaponization of the Dollar

- Sanctions and political tensions, like those between the U.S. and countries such as Russia and China, may push these nations to find alternatives to the dollar to reduce their dependency.

- The formation of trade alliances and alternative payment systems (e.g., BRICS nations using non-dollar currencies) could accelerate the trend toward dedollarization.

- If these nations successfully establish trade networks that exclude the dollar, it would decrease global demand for the currency, contributing to its depreciation and inflationary pressures in the U.S.

8. Global Diversification Away from the Dollar

- Central banks around the world are increasingly diversifying their reserves, allocating more to gold and other currencies as a hedge against dollar devaluation.

- If major holders of U.S. debt (such as Saudi Arabia or China) decide to shift even a fraction of their dollar holdings into other assets, it could trigger a broader shift, leading to a reduced demand for the dollar globally.

- A weakened dollar would result in higher import costs and inflation within the U.S., potentially leading to a stagflation scenario (high inflation combined with stagnant growth).

9. Commodity Pricing Shifts

- Commodities like oil are currently priced in dollars globally, which supports demand for the currency. If major oil producers like Russia or OPEC nations decide to start pricing oil in other currencies (e.g., Euros, Yuan), it would reduce the global utility of the dollar.

- A shift away from "Petrodollars" would reduce international demand for the USD, leading to its depreciation.

- This would further drive up import costs and contribute to inflation, particularly in energy prices, which would ripple through the broader economy.

10. Increased U.S. Reliance on Debt and Risk of Default

- If debt continues to grow and interest payments become unsustainable, the U.S. might face the risk of a technical default, where it fails to meet its obligations temporarily due to political gridlock or fiscal mismanagement.

- Even the risk of default could lead to a credit rating downgrade for U.S. debt, causing yields to rise sharply and reducing the dollar’s attractiveness as a safe asset.

- This would trigger inflationary pressures as borrowing costs skyrocket and the dollar’s value declines further, creating a potential run on the currency.

11. Domestic Pressure for Monetary Policy Adjustments

- Rising debt can constrain the Federal Reserve’s ability to raise interest rates when needed. If inflation is high but debt levels make raising rates politically difficult, it creates a policy trap.

- Inability to raise rates can exacerbate inflation, leading to a loss of control over monetary policy.

- Conversely, if rates are raised too quickly to combat inflation, it could lead to a debt crisis, where the cost of servicing the debt becomes unsustainable, triggering a fiscal crisis and rapid currency devaluation.

Conclusion

The risk of record inflation and dedollarization is not immediate but is a serious long-term concern if the U.S. does not address its growing national debt. A combination of excessive debt monetization, loss of global confidence, and shifts in geopolitical power could create a perfect storm that weakens the dollar’s position as the world’s reserve currency, leading to severe inflation and economic instability. Addressing these risks will require careful fiscal and monetary policy management to ensure the sustainability of U.S. debt levels and maintain global confidence in the dollar.

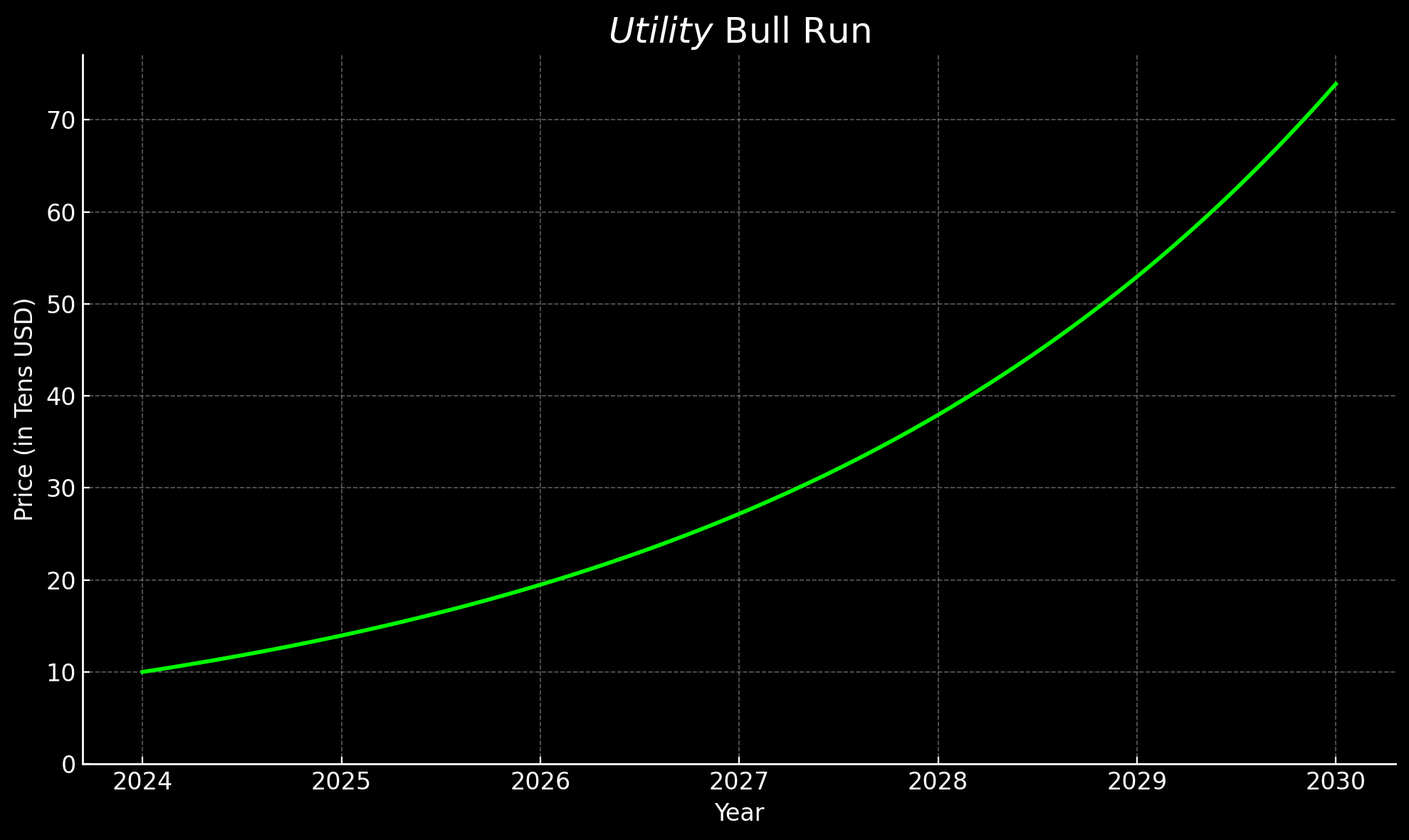

Learn to Invest in Order to Offset Inflation

-

Investing in utility-driven assets, such as utility-driven cryptocurrencies, can help offset inflation in various ways by leveraging their unique characteristics and economic models. Here's how and why such investments might serve as an effective hedge against inflation:

1. Intrinsic Value from Real-World Use

- Utility-driven assets are often tied to a specific service, technology, or ecosystem, providing them with intrinsic value beyond speculation. For example, these assets can represent access to technology platforms, payment for services, or governance rights in a decentralized system.

- As demand for these underlying services or technologies grows, the value of the utility asset tends to appreciate, potentially outpacing inflation. This appreciation serves as a counterbalance to the declining value of fiat currency.

2. Supply and Demand Dynamics

- Many utility-driven assets have a fixed or limited supply, making them inherently deflationary. When the supply is capped and demand increases, the price of these assets can rise, making them valuable stores of wealth.

- This contrasts sharply with fiat currencies, which can be printed or inflated at will, reducing their value over time. Thus, holding limited-supply utility assets can act as a hedge against the eroding value of traditional currencies.

3. Decentralization and Reduced Central Bank Influence

- Utility assets often operate outside the control of central banks and governments. Because of this, they are not subject to policies that can lead to currency devaluation, such as excessive money printing or artificially low interest rates.

- This independence from central bank influence means that the value of utility assets may be more resistant to inflationary pressures compared to traditional financial instruments.

4. Yield-Generating Capabilities

- Some utility-driven assets offer yield-generating opportunities through mechanisms like staking, lending, or other forms of passive income within their ecosystem.

- These yields can potentially exceed the inflation rate, allowing investors to maintain or even increase their purchasing power. For example, if inflation is at 4% but a utility asset generates a 10% annual yield, the real return is still positive, effectively offsetting inflationary effects.

5. Intrinsic Scarcity Mechanisms

- Certain utility-driven assets incorporate scarcity mechanisms like periodic reduction of new issuance or transaction-based burns that remove portions of the asset from circulation.

- Such mechanisms can create deflationary pressure, meaning that the asset's value may increase as its supply diminishes, making it a potential inflation hedge.

6. Global Accessibility and Stability

- Utility assets are often globally accessible, allowing people in countries facing severe inflation or currency instability to convert their wealth into a more stable asset.

- This global demand, especially in regions experiencing high inflation, can increase the value of these assets, making them attractive as hedges against local currency depreciation.

7. Diversification of Investment Portfolio

- Including utility-driven assets in a diversified investment portfolio can mitigate the overall impact of inflation. Because these assets often behave differently compared to traditional stocks or bonds, they can provide a hedge against inflationary periods.

- Their value may rise during times of economic uncertainty or when fiat currencies lose value, balancing the portfolio's performance.

8. Enhanced Security Against Monetary Devaluation

- When fiat currencies are devalued, holding assets that have real utility and intrinsic value can preserve wealth. Unlike speculative assets, utility-driven investments tend to maintain demand due to their inherent functionality.

- For example, assets that enable cross-border transactions, provide access to cloud storage, or facilitate decentralized operations may still be needed even if inflation is high, ensuring steady value retention.

Considerations and Risks

While utility-driven assets have potential as an inflation hedge, they are not without risks:

- Volatility:

- Regulatory Uncertainty:

- Adoption and Usability:

- Technological Risks:

Strategic Use in an Investment Portfolio

To effectively use utility-driven assets to offset inflation, consider the following strategies:

- Focus on Established Utility: Prioritize assets with proven utility and adoption. Assets that solve real-world problems and have established user bases are more likely to retain value in inflationary environments.

- Yield-Generating Opportunities: Look for yield-generating mechanisms within the ecosystem to counterbalance inflation. For example, staking or lending within the network can provide returns that keep up with or exceed inflation.

- Diversify Within Utility-Driven Assets: Just as with any investment strategy, diversification is key. Hold a mix of utility-driven assets that cover various sectors (e.g., decentralized storage, finance, governance) to spread risk and exposure.

Final Thoughts

Utility-driven assets have the potential to offset inflation due to their unique value propositions, scarcity mechanisms, and independence from traditional financial systems. When carefully selected and integrated into a broader investment strategy, these assets can serve as an effective hedge against inflationary pressures, providing value stability and potential appreciation in times of economic uncertainty.